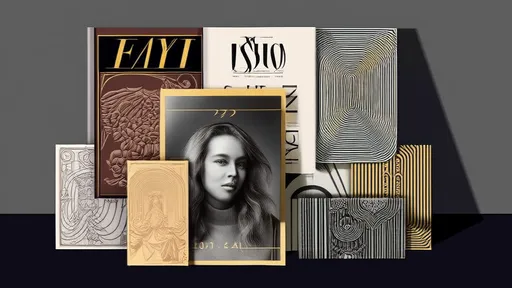

The glossy pages of fashion magazines have long served as cultural time capsules, capturing not just sartorial trends but the very essence of societal evolution. Over the past century, these covers have transformed from straightforward product displays into complex visual narratives that reflect shifting ideals of beauty, power, and identity. What began as utilitarian advertisements for department stores blossomed into an art form where photography, illustration, and graphic design collide with zeitgeist.

In the early 1920s, fashion magazine covers resembled Edwardian calling cards rather than the bold statements we recognize today. Delicate hand-drawn illustrations dominated, featuring women with rosebud mouths and elongated necks swathed in fur-trimmed coats. These covers whispered rather than shouted, their muted watercolor palettes and intricate Art Nouveau borders reflecting postwar conservatism. The models—if one could call them that—rarely made eye contact with viewers, their demure poses mirroring societal expectations of feminine propriety. Vogue's April 1923 cover typified this era: a society woman in cloche hat glancing sideways, her profile framed by cherry blossoms as if afraid to confront the reader directly.

The seismic cultural shifts of the 1930s shattered this restraint. As photography began supplanting illustrations, covers gained a newfound immediacy. Black-and-white portraits by Horst P. Horst and George Hoyningen-Huene presented fashion as high art, their dramatic lighting sculpting models into modern-day goddesses. Harper's Bazaar's legendary 1934 "Mainbocher Corset" cover captured this transition—a stark, almost clinical study of back-lacing ribbons that celebrated the female form while rejecting Victorian modesty. This was the decade when fashion covers stopped merely depicting clothes and started selling fantasies.

Postwar optimism in the 1950s birthed what we now recognize as classic magazine glamour. Richard Avedon's kinetic photographs for Harper's Bazaar showed models mid-laugh, their full-skirted Dior gowns frozen in motion against candy-colored backgrounds. The covers became brighter, bolder, dripping with the era's exuberant consumerism. Unlike the anonymous society women of earlier decades, faces like Suzy Parker's and Dorian Leigh's became recognizable brands themselves—the original supermodels. This was fashion journalism's golden age, when a single cover could dictate global trends without apology.

Radical social changes in the 1960s and 70s turned covers into protest signs. Diana Vreeland's psychedelic Vogue spreads mirrored the counterculture's rejection of establishment values, featuring Twiggy's kohl-rimmed eyes staring defiantly through a kaleidoscope of Op Art patterns. The August 1970 issue of Harper's Bazaar famously declared "The Natural Woman," its cover model's frizzy hair and minimal makeup challenging decades of polished perfection. These weren't just magazines—they were manifestos printed on glossy stock.

Excess defined the 1980s covers, with their DayGlo colors and shoulder-padded power suits. Italian Vogue's 1988 "Supermodel" cover featuring Linda, Christy, and Naomi didn't just showcase clothing; it sold ambition, sex, and unapologetic wealth. The models stared down the lens like corporate raiders, their bronzed limbs and wind-tossed hair embodying Reagan-Thatcher era materialism. Art directors embraced bold typography that competed with the imagery, creating visual noise that mirrored the decade's maximalist ethos.

Digital manipulation in the 1990s created covers that were more concept than reality. Kate Moss's 1993 "waif" cover for The Face, all ghostly pallor and androgynous styling, sparked debates about beauty standards that still resonate today. Meanwhile, David LaChapelle's hyper-saturated, surreal compositions for Interview Magazine turned models into pop art installations. The line between fashion photography and digital art blurred irrevocably during this period.

Contemporary covers exist in a paradox—simultaneously more inclusive yet more manipulated than ever before. The 2010s saw watershed moments like Vogue Arabia's first hijab-wearing cover model and British Vogue's 2020 all-black lineup. Yet behind these progressive images lies increasing reliance on AI retouching, creating impossible standards even as diversity expands. The rise of celebrity self-shot covers during COVID-19 lockdowns—think Lady Gaga's 2020 Vogue Hommes spread photographed via iPhone—suggests an industry grappling with authenticity in the digital age.

What remains constant across these transformations is the fashion cover's unique power to distill complex cultural moments into single, arresting images. From the hand-painted florals of the Jazz Age to today's algorithmically perfected compositions, these pages continue to reflect our deepest aspirations and anxieties about identity, status, and self-expression. The next century of covers will undoubtedly rewrite the rules again—but their ability to captivate and provoke seems eternal.

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025